The Netherlands is the perfect example of a country with a long history of places that inspire a fierce sense of pride.

When I first arrived here, I stood at an intersection in Amsterdam and watched the city flow in front of me and had an epiphany. I saw how everyone–including pedestrians, cyclists, and car drivers–knew what to do and how to respectfully interact with each other, even without stoplights or traffic signs. And even though the compact streets were busy, there were no honking horns or road rage to be found.

Then I looked down and saw the loose-set bricks that allowed simplified street maintenance. I also noticed how there were no police around because there was nothing going on that required policing. People were just getting along with each other and enjoying themselves in their normal everyday lives. From their perspective, this is all nothing special. But for me, it was a window to a whole new world.

And in my head, I was comparing the numbers and budgets associated with the sprawling, high-maintenance places I’d come from to the numbers of the far more functional place I was standing in. It was a radicalizing moment because I could clearly see the interrelationship between the design of a place and its performance, and how pathetically low my standards truly were. Once I saw this, I could never unsee it.

Quantifiable Urban Topology To The Rescue

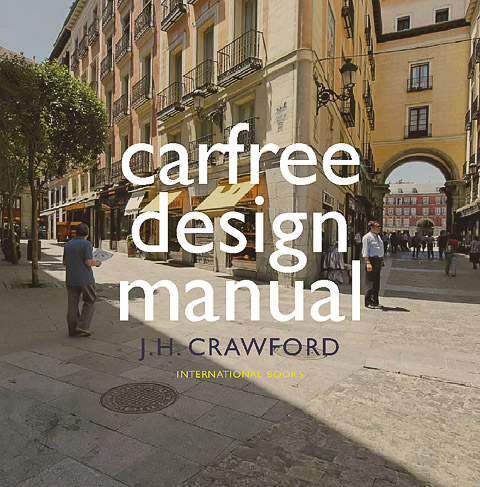

While looking for a way to help explain these issues, I found the book Carfree Design Manual. The author, Joel Crawford, who also wrote the book Carfree Cities, is an American who had a similar epiphany and also decided to make his home in the Netherlands.

An explorer, designer, and engineer, Joel’s thorough research led him to create a sort of algorithm that describes the essential common attributes and dimensions found across the world’s great historic carfree places.

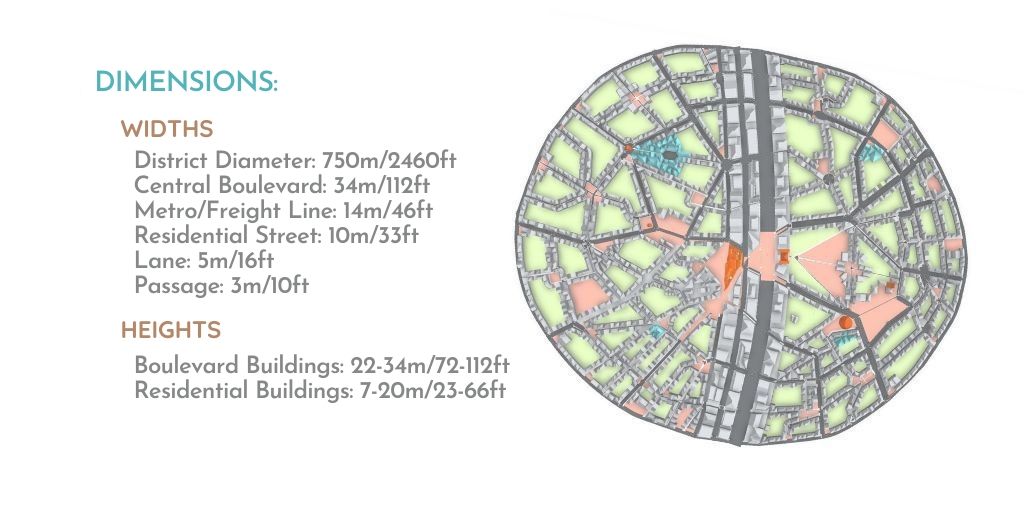

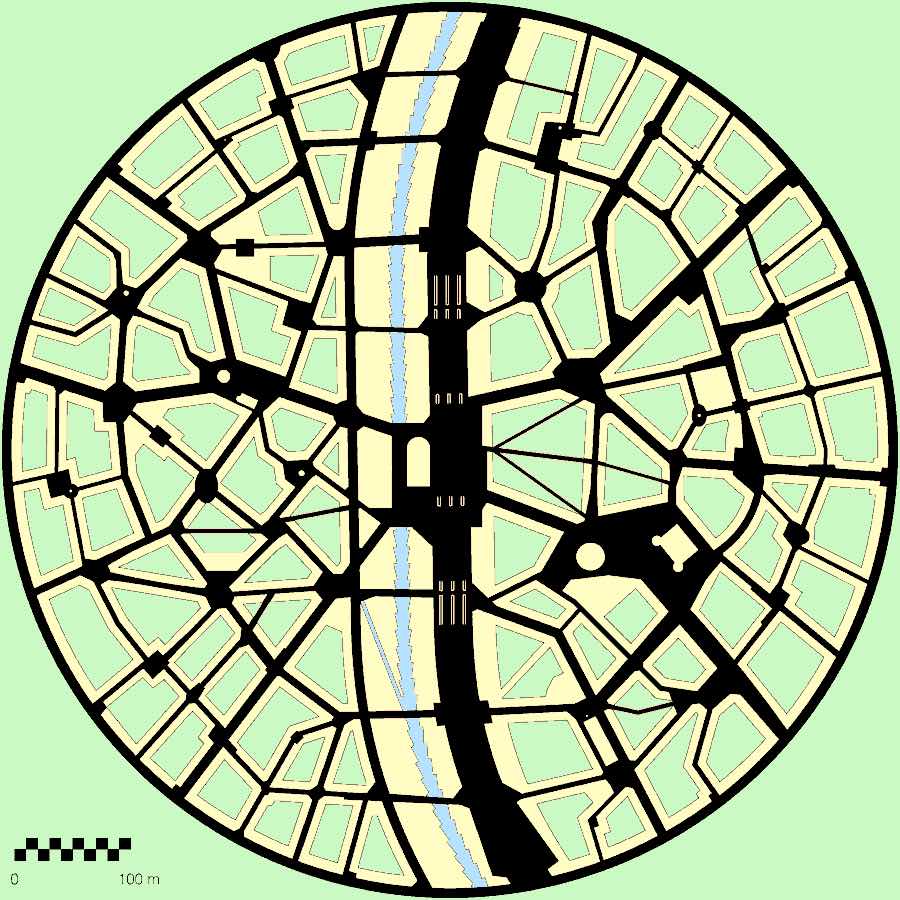

This sort of algorithm, which he calls the “Carfree Reference District”, it’s not an actual place, but a conceptual topology to help visualize and quantify some of the basic patterns and rules of carfree places. It’s a model for compact, non-sprawling development that creates community and prosperity while also conserving the countryside around it.

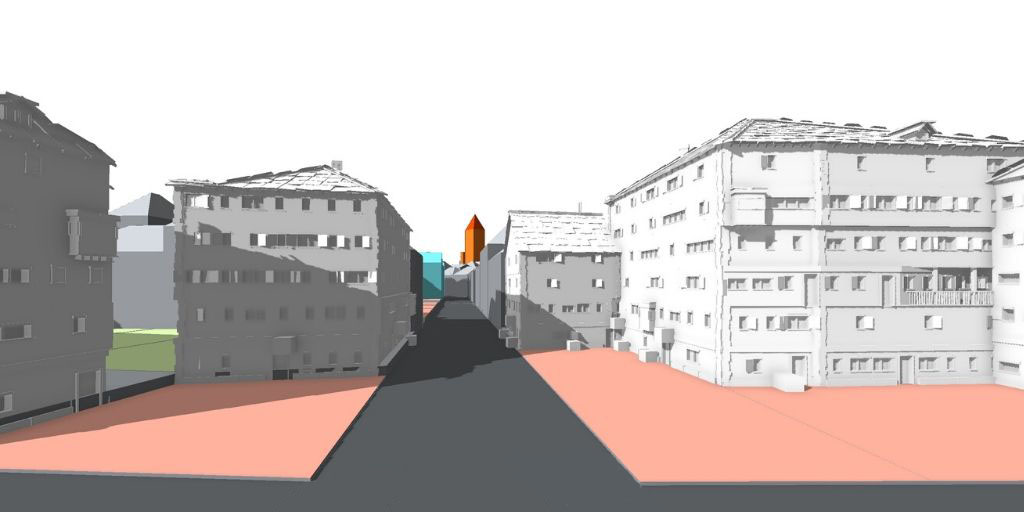

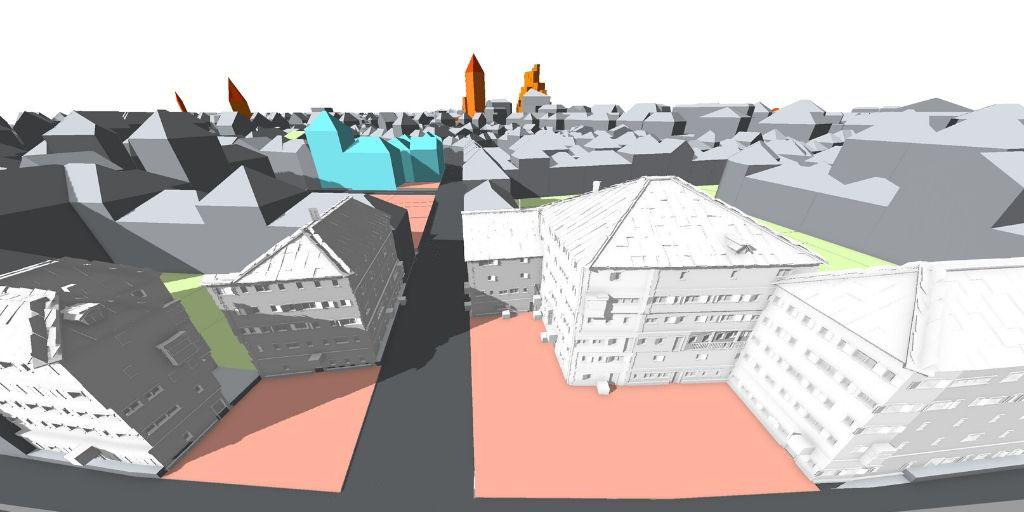

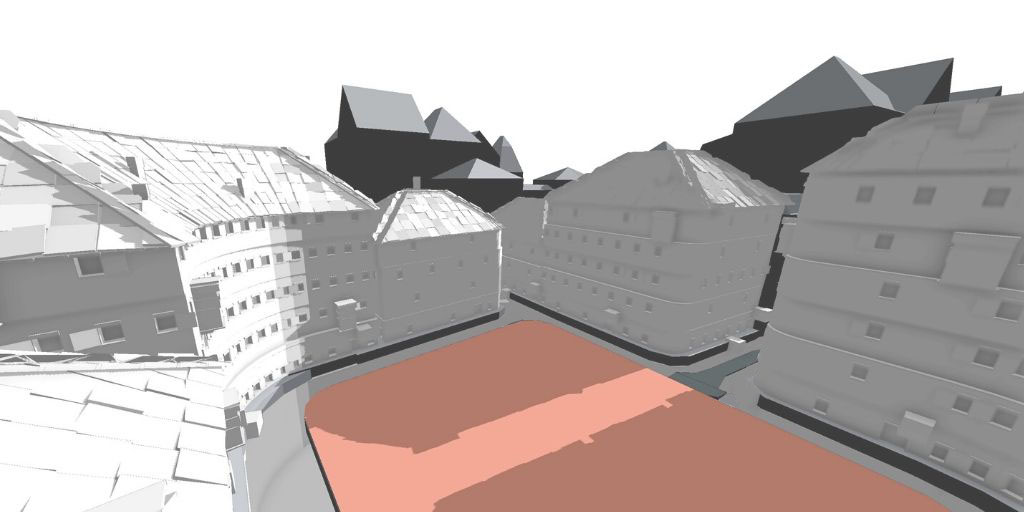

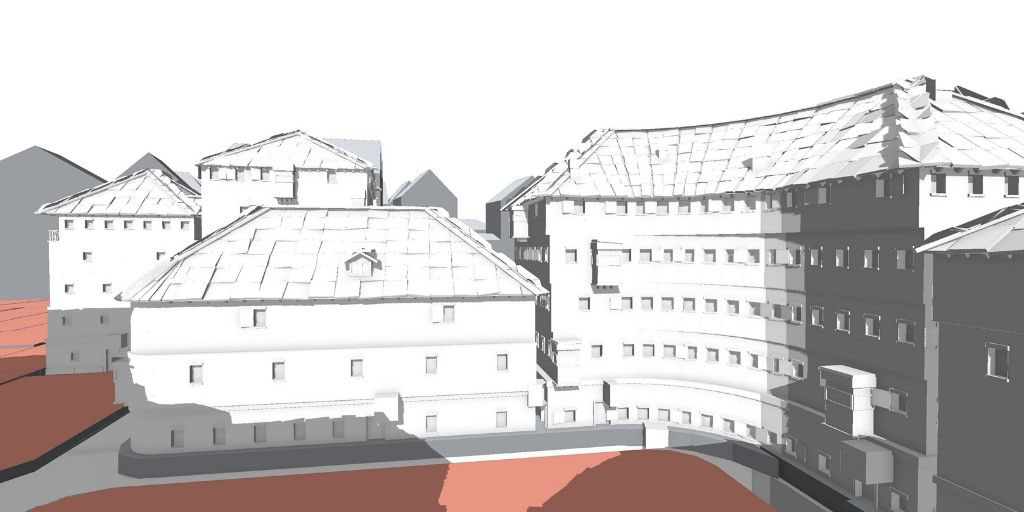

At B4place, we were so inspired by Joel’s systematic approach that we created a 3D version of his model to help show the spatial relationships between the elements.

In our renderings, the peach areas are public spaces, green shows the greenspace and gardens, dark grey is roads, light gray is common buildings, orange is special buildings, and blue shows the arcaded shopping areas.

Some key elements of the Carfree Reference District include:

- Unique districts: Streets are usually gently curved, and a number of small to medium-sized squares prevail, with distinct characteristics and patterns of squares and buildings.

- Radial design: Radial designs minimize walking times to the center, where the transportation hub is located.

- Narrow streets: The streets in the reference district average 25 ft (7.5 M) wide. Varying the width along the street adds interest.

- Mixed uses: Another must for a community-oriented place is to vertically mix commercial and residential uses, which adds 24-hour life to a place.

However, a carfree district in the real world would look different from Joel’s plan and our 3D model, even if the patterns and rules were followed to the letter, because real places have unique constraints and considerations.

The Carfree Reference District can be used like an “urban transect”–an informational tool to guide the design of a place. While the first edition of Carfree Design Manual is becoming harder to find, we hope that community advocates will find a spot for it on their placemaking reference shelf.